How the Nashville Hotel Coffee became a Household Name via the Fabric of American Jewishness.

There’s just no convincing you that Kosher-for-Passover certification is something your customers will care about if they’re, well…not Jewish. Which, if you’re like most food companies, is likely the case. But there’s something to be learned here from the companies (like Kraft Heinz and Pepsico, to name-drop a couple) that choose to undergo this niche certification type each year for some or all of their products. This year, OK Kosher is certifying over 8,500 Kosher-for-Passover products.

Let’s talk about why.

Kosher-for-Passover: It’s Not Your Average Health Claim

We’ll be real with you. Contrary to what you might hear, Kosher-for-Passover is not congruent with gluten-free, grain-free, “unprocessed” or any other health claim. Seriously. Matzah is 100% wheat. That’s full-on gluten-positive (unless you buy the special gluten-free variety made from oat flour). And Kosher-for-Passover is also a far cry from a vegan. Eggs are even more commonly used on Passover. Especially in baked goods to make up for the lack of leavened flour. Meat and chicken are also among the most common Passover holiday fare.

So while some observant folks say their diets are healthier during Passover, this has more to do with the traditional focus on homemade meals. In food manufacturing, on the other hand, Passover certification doesn’t automatically correlate to a healthier option. That’s even when we’re talking about the vast array of grain-free items that get certified for Passover.

Rather, as with Kosher-Certified in general, Kosher-for-Passover is not a health claim, it’s a lifestyle distinction. A product that meets our rigorous standards for this category is totally free of chametz (also spelled chometz, chumetz, etc.). That’s the Hebrew word for leavened food matter resulting from combining grains with water and letting it sit for a while. (Think sourdough, the precursor to industrially cultivated yeast). That’s the only promise here.

It’s Just a Jewish Thing

It’s well known, and we talk about it a lot: that regular, non-Passover, kosher certification is a win-win. Because for eligible companies, regardless of sub-market, consumers want it. Whether or not their customers ascribe to a certain religious or cultural background, kosher tends to stand out and stick.

While we can’t pinpoint exactly what kosher means to every consumer, the data out there is telling. Most consumers prefer a kosher certified product over a corresponding, uncertified one on the shelf. (We have lots of reading material on this, such as here and here). In fact, major retailers’ marketing teams plumb the depths of online forums and social media groups to research what kosher consumers want to see on the shelves.

But this is different. Clearly, Kosher-for-Passover doesn’t seem to strike the fancy of the general public in quite the same way. Most Kosher-for-Passover foods get relegated to the “International Foods” aisle. Or better yet, the Passover aisle in the supermarket a few weeks before the festival. Because – let’s face it – Passover is a pretty Jewish thing.

We’ll even take that fact a little bit further. Passover is arguably the time on the Hebrew (i.e. lunar, Jewish) calendar when Jews of all backgrounds congregate and observe holiday traditions most.

To be clear, American Jewry is varied and, in many cases very cultural but decidedly irreligious. In fact, according to a 2013 Pew Research study, 70 percent of adult American Jews participated in a Seder in the year prior. But only 31 percent are members of a religious congregation.

If that sounds contradictory, let us explain. People commonly refer to Judaism as a religion. So what is a Jew, if not for said “religious congregation” to identify as a part of? Without reopening a well-worn philosophical discussion, suffice to say this. For the vast majority of American Jews, and a good deal of those worldwide, being Jewish is primarily a cultural identity, and secondarily (if at all) a religious one.

But there are times when the waters that seem to divide the Orthodox and the strictly cultural Jewish contingents seem to somehow, just…part (had to). And Passover is number one.

As an undeniably religious institution, we at OK Kosher see the two definitions – cultural and religious – as inherently intertwined. That’s part of our ethos as an organization and is the main inspiration for our work. And although many Jews don’t consider their own religious and cultural identities as aligned or even related, the clear disruptor to that mindset is Passover.

Although many Jews don’t consider their own religious and cultural identities as aligned or even related, the clear disruptor to that mindset is Passover.

Hang on there, keep reading. Yes, even you companies whose brands don’t focus on the “Jewish Market,” hear us out! Here’s where it gets interesting. For a fleeting eight days this April (it’s usually in April), your teeny, tiny Jewish customer base will mean a lot more to your sales than it ever will. Just take it from Maxwell House.

A Niche Americana

Yes, that Maxwell House. What’s so Jewish about an actually non-Jewish, southern coffee company? This month, we interviewed Elie Rosenfeld, CEO of Joseph Jacobs Advertising: the ad agency that “discovered the Jewish Market” 100 years ago this year. That’s also the agency that created the original ad campaign for Maxwell House targeting the Jewish community in 1919. Four years later, the Maxwell House Haggadah came along and became as American-Jewish as macaroons and the White House seder eventually would.

So if you’re not familiar with the Kosher-For-Passover Maxwell House story already, then this is the place to be. If you are, this is still the place to be because there’s a lesson here for your company too.

It’s the story of how one of the first US coffee roasters entered the canon of Jewish American nostalgia – and stayed there. Think Norman Rockwell’s Thanksgiving painting, but with some of the people sitting around the table wearing yarmulkes, one dipping parsley into salt water, and the master of the house hiding pieces of broken matzah under an embroidered cloth.

So we asked Mr. Rosenfeld to take us back to the beginning. Where did this story start? And what exactly does a “Jewish Marketing Company” do anyway? And why? Here is what we learned.

From Niche Salesman to Big-Time Ad Executive

Joe Jacobs, the founder of Joseph Jacobs Marketing, cut his PR teeth selling ads for the Jewish Daily Forward. That’s the iconic Jewish newspaper founded in 1897, originally called The Forverts and written in Yiddish. It was a formative part of Jewish culture around the turn of the century. The Forward still publishes today, primarily in English, online and in print.

While there, Jacobs provided similar services to about a dozen or so other newspapers based in New York. This led him to expand to serve publications catering to the general public, not just the Jewish community. The success from that led him to found the Joseph Jacobs Advertising firm in 1919. Joseph Jacobs Advertising is now a full-blown creative marketing agency. They still focus on liaising between that Jewish-centric market and the brands that want to hone in on it. (For reference, Amazon is one of their clients for their collaboration with Manischewitz on a The Limited Edition Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Macaroons and accompanying Midge’s Haggadah).

Maxwell House: From Nashville Hotel to Household Name (via New York)

Originally, Maxwell House Coffee was named Cheek-Neal Coffee Company after its founder Joel Cheek. Their unique selling proposition was to offer pre-roasted coffee beans. This was at a time when most people roasted and ground green coffee beans at home. Maxwell House was the name of a successful hotel in Nashville, Tennessee that served the popular coffee to its guests. Due to popular demand from the hotel’s patrons, Joel Cheek decided to brand his coffee as Maxwell House Coffee. This led him to take manufacturing to the national level. But in order to do so, they needed an entrance into the market, and a solid marketing plan.

So when Maxwell House teamed up with Joseph Jacobs, the angle was clear. That entrance? New York City. And one major gateway into the New York market, Jacobs emphasized, was its large Jewish population.

This was before the postwar suburban sprawl of the 1950’s, when people lived shoulder-to-shoulder on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Like other tight-knit immigrant groups in the city, the Jews had a rich language and a cultural palette of ethnic cuisine. Which are challenges that any food or beverage brand would need to surmount. But a hurdle that no other minorities posed was a set of stringent dietary laws on top of that: Kosher. Without the ability to assure Jewish consumers that their products were kosher, the marketing plan would have been a non-starter.

Yet Jacobs was willing to take the challenge to a further level. He felt that in order to position Maxwell House coffee as kosher to consumers, they had to go for Passover. He was a member of the Jewish community himself. So he honed in on what traditionally observant and modern American Jews alike would need to see. In order to buy, they’d need assurance that the new products they were coming to love were absolutely kosher-for-Passover according to the authorities. And once on the Passover table, Maxwell House would have a place in the hearts of Jewish consumers.

Jacobs knew that the emotional connection would build nostalgia forged through memories with friends and family during the holiday. In addition, this type of targeted marketing was a completely new arena. Maxwell House had the opportunity to jump in early on what would become a longstanding strategy.

In order to position Maxwell House coffee as kosher to consumers, they had to go for Passover.

Now let’s back up a moment. This was before kosher certification even existed, let alone Passover-specific. Common practice in the community was to trust the Jewish butcher and baker with selling the same level of kosher goods they’d feed to their own families. Furthermore, the religious and cultural norm at the time was for even the most basically observant Jews to only eat homemade foods on Passover. Back in Eastern Europe, where the majority of New York’s largely Ashkenazi Jews were from, coffee wasn’t really a thing – tea was. So while coffee certainly made its way into the homes of assimilating American Jewish families, there wasn’t necessarily enough knowledge about it to ‘OK’ coffee for Passover.

A Bean by Any Other Name

Not yet, anyway.

There was one potential roadblock in this foray into Jewish dining rooms. If anyone was wondering whether coffee was Passover-appropriate, the thought process was simple. Coffee comes from coffee beans. Beans fall under a category called Kitniyos (or Kitniyot in the Sephardic pronunciation). Which is something Ashkenazi Jews customarily don’t eat on Passover.

So coffee was a no-go?

Not so!

The campaign set out to clarify something the majority of Eastern European Jewish immigrants weren’t aware of. That is, coffee beans are not beans at all. They’re the seed of a berry. That’s right, the Coffea plant is a fruit-bearing one whose berries (referred to as cherries) have a seed that we all call the coffee “bean.” Simply because that’s what it looks like – a bean. And like any berry or cherry (or their seeds), coffee is kosher for Passover.

Coffee beans are not beans at all. They’re the seed of a berry. And like any berry, coffee is kosher for Passover.

The next step was to figure out how to convince the more stringent in the community of this fact. How would they assure people that it was fine to have coffee on Passover? And most importantly, how would they entice them to go out of their comfort zones? Adding pre-roasted coffee from a non-Jewish manufacturer to their diets of sanctioned American pleasures was a new frontier. So he hatched a plan and, like any good marketer, developed a campaign in their language – literally and figuratively.

In March of that year, The Forverts printed advertisements

proclaiming Maxwell House’s appropriateness for Passover – in Yiddish. With ad copy like: “Mitzvah aleinu lisaper: Maxwell House Coffee iz Kosher L’Pesach,” translation: “It’s a mitzvah to tell you: Maxwell house is kosher for Passover!” And “Bli shoom chashash, mehadrin min hamehadrin,” Free translation: “Without any doubt, kosher to the highest standard.”

Even the company logo was translated into Yiddish: “Gut Beyzen Liatztan marapen,” Good to the last drop™.

They even went so far as to collaborate with a well-known Rabbi to endorse the product. With this, they could advertise a conventional product to kosher-keeping Jews in a meaningful way. Rabbi Betzalel Rosen was enlisted for the task, and gave his haskama – official approval – for Jews to drink Maxwell House coffee on Passover. His name was even stamped on some of the ads, providing unmistakable assurance.

Norman Rockwell for the Jews

But a question remains. Why so much effort just to appeal to Jews? Simply put, it was an untapped market, and a relatively large slice of the New York market. Untapped, because most Jewish people simply didn’t have manufactured products on Passover before that.

Furthermore, Passover is essentially the Jewish Thanksgiving. For Jews, it’s huge. So Joe Jacobs’ strategy went like this: Passover is the quintessential holiday where Jews collectively celebrate heritage, family, culture, miracles, freedom, and of course, food. Enter said nostalgia we mentioned. And since they’re an untapped, large piece of a key market (New York), it’s worth a shot trying to get a place at that table. In fact, Tropicana Orange Juice (Pepsico) and Philadelphia Cream Cheese (Kraft Heinz) have learned that the eight-day holiday actually does affect sales.

This is because it’s the most widely celebrated Jewish Holiday. Even more so than the most “important” ones – Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah – as evidenced by findings from Pew Research that:

“While only 23% of U.S. Jews said they attend religious services at least monthly, 70% said they participated in a Seder last year…Participation in a Seder is more common among Jewish Americans than any of the other practices we asked about, including fasting for all or part of Yom Kippur (53%) – often considered the holiest day of the Jewish calendar – and always or usually lighting Sabbath candles (23%).”

For instance, it’s not uncommon for even those who don’t consider themselves religious to restrict themselves to Kosher-for-Passover foods during this time. The same often goes for people who only have one Jewish parent or grandparent. That’s not to mention some who dabble in Passover observance to varying levels each year. These types tend to high-tail it to the Passover aisle in the supermarket before making any other menu plans. These may be young singles or couples who live far from their parents and don’t belong to congregations. In the absence of a family or community Seder, they seek out undoubtedly Passover-appropriate fare they can find easily in the stores.

The nature of the holiday’s backstory inspires this tendency. So does the communal tradition of some synagogues to hold a large Seder. These meals are open to people far beyond members (like the record-breaking Chabad of Nepal Seder each year). Organizers allow nary a morsel of food on the table that isn’t completely kosher-for-Passover, and certified at that. This accounts for a significant chunk of Kosher-for Passover-certified buying.

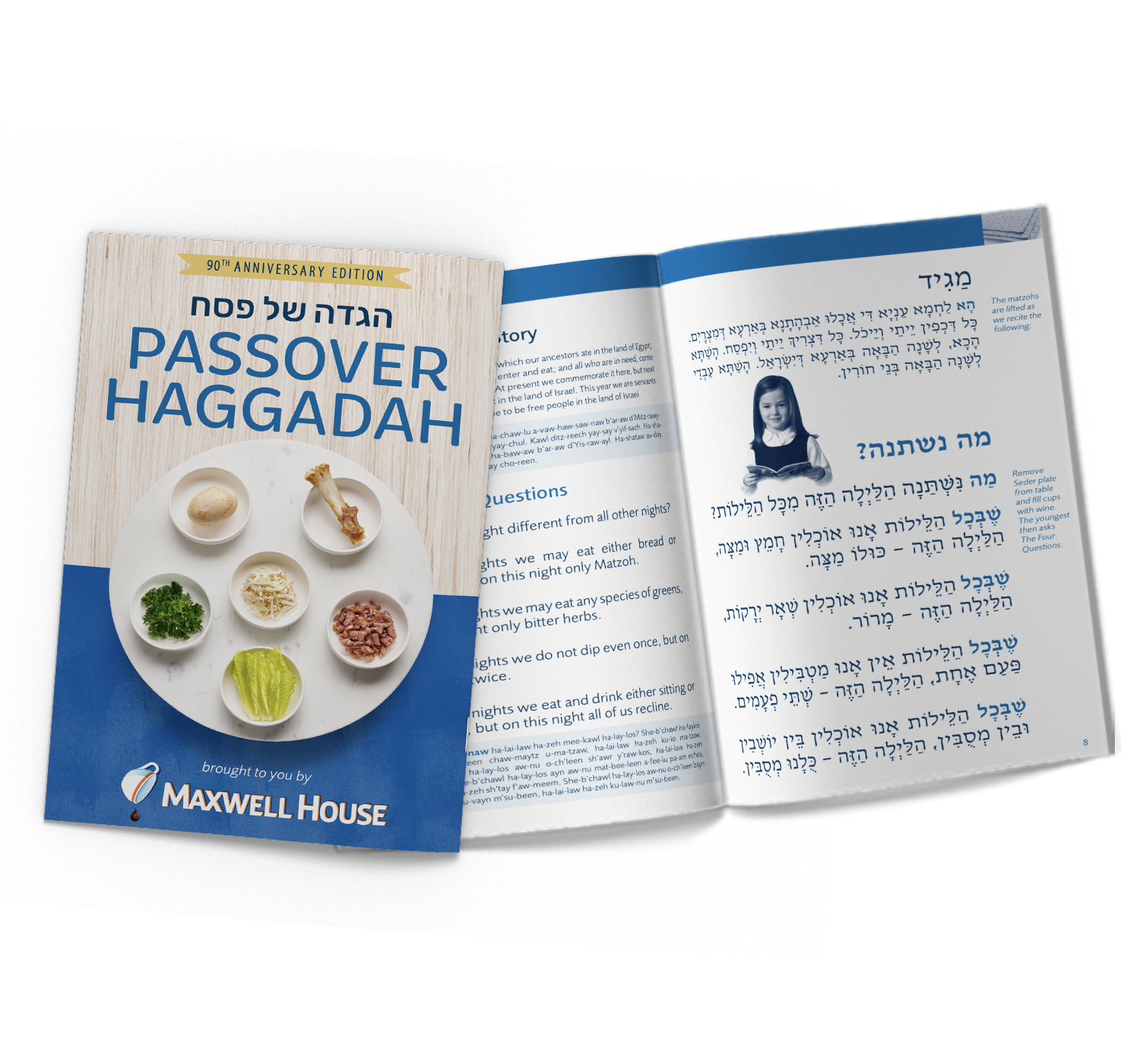

A Bold Proposition – The Maxwell House Haggadah

The Passover holiday’s message centers around a basic religious commandment. That is, for Jews to remember the Exodus from Egypt specifically through retelling the story, especially to the next generation.

The Haggadah is a multifaceted text comprised of the scriptural Exodus story peppered with Rabbinic exposition and instructions for observance. Why on earth, then would Maxwell House concern themselves with a project intertwined with Torah observance to this degree?

The Haggadah is a multifaceted text comprised of the scriptural Exodus story peppered with Rabbinic exposition, and instructions for ritualistic observance.

It seems Jacobs figured that, if you’re going to go for the specialized, ultra-niche market, then really go for it! So he drummed up the idea to publish a new Haggadah with Maxwell House’s branding on it. This would be the surefire way to cement their image into the minds and hearts of Jewish Americans. Then New Yorkers as a whole. And then the rest of the USA. The Haggadah was included as a free gift with the purchase of a Maxwell House coffee can in the month of March. Thus the publication wove itself into the fabric of American Jewishness.

A Haggadah for the Generations

Whatever kind of Passover someone will have this year, and whether or not they drink Maxwell House, this story certainly proved one thing. That is, that when a brand participates in treasured, memorable traditions, it stays there. In the hearts and minds of the people and families who have it for a time-honored ritual.

Today, Elie Rosenfeld conducts a mock Seder every year in the Kraft Heinz Company headquarters in Chicago. (For the past two years, it was done remotely because of COVID-19). He organizes a kosher-catered meal, sets out the finest disposable dishes and cutlery, and sets up a traditional Seder plate of commemorative foods: An egg, a roasted bone, a vegetable to dip in salt water (representing the tears of slavery), marror (horseradish paste commemorating the bitterness of slavery) and charoset (a sweet paste of nuts, fruit and wine, resembling the cement that the slaves used to make bricks for the Egyptian Pharaoh). On the way, he stops off at a grocery store to pick up some well-known products that have a Kosher-for-Passover certification mark on them, including Kraft Heinz products as well as others.

Mr. Rosenfeld tells me that Kraft Heinz shared with him that they see the Haggadah as a cherished part of their brand image to this day.

History Comes Full Circle (OK)

Fast-forward about ten years or so, and you have the formation of OK Kosher Certification, then called Organized Kashrus Laboratories (OK Labs for short). By the 1930’s, kosher certification had already been established as a new way to bridge the gap between rabbi-supervised products and the kosher consumers wondering if they could eat them.

As one of the pioneers in overall kosher certification, as well as high standards within that niche, OK Kosher appealed to Maxwell House as a company. And today, as a brand of Kraft Heinz, the OK symbol (along with that little P for Passover next to it) continues to assure today’s most religious Jews that the product is indeed Bli shoom chashash, mehadrin min hamehadrin – Without any doubt, kosher to the highest level for Passover.

Legend even has it that one of the originators of OK Kosher, Mrs. Thelma Levy, of blessed memory, had a hand in creating the Maxwell House Haggadah.

The Power of the Seder

There’s an expression about the Jewish Sabbath (Shabbat or Shabbos) that, “More than Jews keep (i.e. observe) Shabbos, Shabbos keeps the Jews.” It’s a statement about how the Jewish people’s rituals have set them apart. And how, throughout history, it’s even kept them alive both physically as a cohesive people, and spiritually, from assimilating into the mundanity of the work week. Perhaps there’s a connection here with our story as well. More than American Jews have kept Passover, The Maxwell House Haggadah has kept American Jews: together, and celebrating.

Okay, maybe that’s a bit miraculous-sounding.

But in my research before this interview, I came across an article that described the Maxwell House Haggadah as the least authentic part of Passover (to paraphrase). So I asked Elie Rosenfeld what he thought of that. He said to me, “the Maxwell House Haggadah has kept American Jews keeping Passover. Full stop.”

He added that it was a free, all-inclusive pamphlet containing every aspect of the Seder’s text and rituals. Because of this, the scores of Jewish Americans who were slowly assimilating out of the fold, retained generations of knowledge on how to celebrate Passover. “Without it, Passover would have been devoid of any ritual whatsoever within a few short years. It’d be down to one glass of wine, a cup of Elijah, a box of Matzah, and a Turkey.”

Further, he shared that the Maxwell House Haggadah has shown up across the country in the most unexpected places. Like prisons, battlefields, and beyond. And it isn’t showing signs of being discontinued any time soon. In fact, you can order a free copy from Joseph Jacobs (just pay S&H) here.

Freedom to be Kosher (for Passover)

We might be willing to assert a spiritual connection between the retelling of the Exodus and the dissemination of the Maxwell House Haggadah. Perhaps that the Jews came out of Egypt through split water to pursue spiritual and physical freedom, and the Maxwell House Haggadah broke through cultural boundaries to unite a people in faith, and promote a very good cup of coffee.

Okay, okay, maybe that’s also a stretch. Either way, we here at OK Kosher wish a happy, healthy and kosher Passover to all who celebrate (and even those who don’t…or are thinking about it!).

Certifiably Kosher-for-Passover – for Your Company

Get your products a seat at the table next year! If you’re interested in pursuing Kosher-for-Passover, or general kosher certification for your company, from Maxwell House’s certification of choice – OK Kosher – click here to get started.

The information presented in this blog post is based on research, general knowledge, and/or the author’s understanding of the subject matter. This blog is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon by the reader or considered as professional advice. For specific guidance on any given topic, the reader should consult a qualified professional in the given field. OK KOSHER DISCLAIMS ANY LIABILITY FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGES RESULTING FROM RELIANCE ON THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THIS ARTICLE.

EN

EN  ZH

ZH  KR

KR  BR

BR  ES

ES  IN

IN  IL

IL